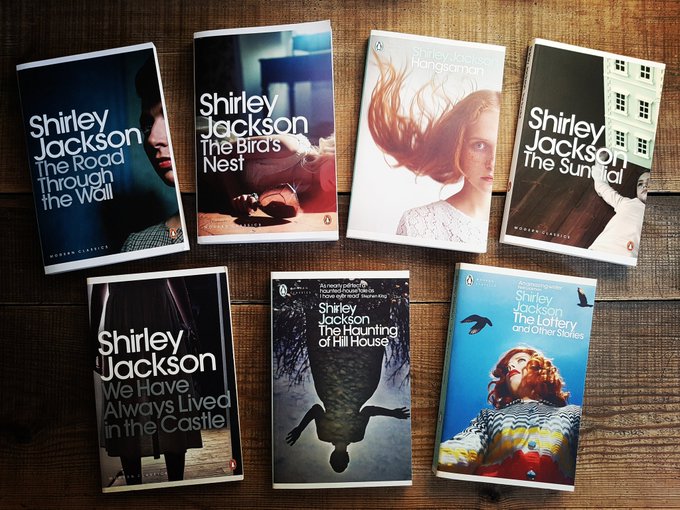

Every one of Shirley Jackson’s books, for me, is a work of art. She’s best known for The Haunting of Hill House, and her short story The Lottery, and to some extent for We Have Always Lived in the Castle, all works I naturally started with myself, but her entire portfolio rarely falls short of these works’ quality.

I mark her books amongst the most consistently brilliant set by any single author in my library – every story memorable in its own right, perfectly, concisely realised. And now I’ve read all her novels I felt it time to rave around them, all the books reviewed under one banner (though mind I still have her two semi-autobiographical works and two more short story collections outstanding – I’ll update this when I’ve got those to add!).

I’ve got a pretty hefty introduction to this article, so if you want to skip straight to each book, use the links below.

Contents

What Makes All Shirley Jackson’s Books Great

Though each of Shirley Jackson’s novels is unique in some way, there are common elements of greatness in most, if not all, of her writing. First, she writes incredibly tight prose; all of her books are relatively short, achieving big ideas and themes with no words wasted. Often, she does this by leaving us to read between the lines, in many cases hinting at actions or clipping dialogue without explicit explanations (done to notable effect in her debut, The Road Through the Wall, where dozens of snippets of conversation feed us just enough to know exactly what the characters are thinking and the implications). This ability to conjure meaningful stories and characters with the bare minimum of detail is one of the most admirable things I believe a writer can do – it doesn’t just take tremendous skill, it takes courage to leave things out and trust the reader to put the pieces together.

Next, in those short spaces she created truly memorable, relatable characters. Her writing often concerns damaged and lonely young women, struggling to fit into society, and there are universally recognisable traits at work with all of them, not least the insecurity of wondering exactly how we fit in. Society, on the other hand, is often shown made up of overbearing, opinionated others. She brilliantly explores awkward feelings which must have gripped us all at some time or other, and her rich internal studies give powerful insights into what goes on beneath the surface of both meek and bold people.

Another running theme in her characters, however, is people’s propensity for selfishness and cruelty. The ease with which people disregard one another, gang up, shift allegiances, all come out hard and fast. Jackson expertly depicts relationships forming and breaking, with minute details within the space of a conversation, and she shows how little societal missteps can lead to big, nasty results.

Connected to this, she also wrote masterful dialogue, with witty back-and-forths that exude character. Considering her often dark themes, her dialogue is lively and playful, making the people that populate these stories vibrant and real. She had a great sense for voice – the characters stand out distinctly, and more often than not they’re recognisable as people from your own life.

Jackson also had a knack for drawing grand, meaningful stories from very humble frameworks, whether it’s a global apocalypse experienced by a handful of entitled layabouts or the difficulties of the human condition demonstrated through a young girl starting college. The stories are close and even claustrophobic, but made grand and important by how much everything means to the characters are their centre. We care a lot about what happens, even the little things, because they matter to much to the characters. No writer, really, can do more than that.

Finally, Jackson’s books share a certain sense of atmosphere and place. They are gothic, gritty and retain that claustrophobic feeling whether set in a suburban cul-de-sac or New York City. We get a feeling for a lurking darkness in all these places, the locations themselves daunting, imposing and never quite friendly. There’s a complicated relationship here, though, as those uncomfortable settings are almost always also very personal, places where the characters truly belong and can, for all the warts, be cherished as familiar.

These are the elements that shine through all her books, but combined they don’t cast every book in the same light; far from it. Jackson wrote, above all, psychological fiction, and in this regard each book really looks at different elements of the psyche, creating a very different feel that, overall combine to a fascinating whole. Those are the similarities, then, what makes each of Shirley Jackon’s books special?

The Road Through the Wall (1948)

The Road Through the Wall is like an anti-Middlemarch – meant in the best way, as this comes from someone with enormous respect for George Eliot. It’s an ensemble piece that puts mid-20th century suburban life under the microscope, the same way Eliot did for provincial society in the Industrial Revolution. It benefits from the same keen insights and carefully chosen interactions that create a broad picture of the residents, their wants, fears, hopes – but it achieves something quite opposite to Middlemarch. Where Eliot’s work is vast and ultimately champions empathy and understanding for your fellow man, Jackson’s is short, sharp and quick to demonstrate how terribly people can treat one another. Her first book, this is also one of her most ambitious, and it’s incredible to see how, maybe here more than ever, she creates an impression almost as much by what is not written. Conversations are clipped, consequences left to interpretation, and the reader is forced to read between the lines – there’s a sense as you do, knowing well enough where certain trains of thoughts are going that they don’t need saying, that we become complicit in the characters’ machinations. The result is something as haunting as it is real.

Hangsaman (1951)

This coming-of-age story follows Natalie Waite going off to college for the first time and is, I think, Jackson’s most unassuming work. There’s a sense throughout that this is a snapshot of life, not a story with a particular trajectory – which is different to how I’ve seen it marketed almost like it’s a thriller about a girl disappearing. It’s a not. It perfectly captures the contrast between a rather sheltered family life and the social politics of young people’s first attempts at independence. The twist in this tale, though, is that Natalie is an outsider, with a vivid imagination, and the book seamlessly slips into her daydreams, adding flashes of the fantasist in Jackson. One sequence towards the end stands out to me as one of the most memorable in all her work – epic, brutal and strange, and yet understated and eerie in the context of the tale. Those asides aside (ahem), Hangsaman is an acutely realised depiction of a young woman finding herself, punctuated with spot-on vignettes of the seedy, manipulative world that surrounds her.

The Bird’s Nest (1954)

I went into this book on the strength of knowing it was Jackson, without reading up on the blurb or story at all, and I honestly think this is the best way to read it. Besides Hill House, this probably comes closer than any of the other books to a genre piece, as something of a psychological thriller, but the less you know the more effectively it’ll work. This one fully embraces the ideas of instability, confusion and madness that are more peripheral in Jackson’s other books, and it makes for a dizzying, captivating (and also occasionally very amusing) ride. The central character Elizabeth at first seems an inoffensive, forgettable young lady, who’s receiving unexplained, nasty notes, but we quickly see that all is not as it seems. The Bird’s Nest has a fantastic sense of voice, and a total trip of a journey into New York – it’s an exploration of identity packed with imperfect characters that jump off the page. Go in without knowing the direction, you won’t regret it.

The Sundial (1958)

The premise of this book probably stood out for me most amongst all Jackson’s book, probably her most recognisably high-concept story (though otherwise only Hill House and, perhaps, The Bird’s Nest, really fall into the brackets of something you could throw quick genre labels at). The Sundial is the story of an apocalypse cult as they approach the end of days, following their shifting relationships in their haphazard preparations for the end. The twist is, it’s not so much a cult as a gaggle of high-society parasites who’ve attached themselves to a self-serving lady on her wealthy estate. The irreverence of the characters, with regards a serious and fearful theme, gives The Sundial at atmosphere of all its own, making it less about the coming doom and more about microcosmic hierarchies and how people manipulate one another. It’s perhaps the ultimate case of a big idea told in a very small, memorable way (and no doubt laid the foundations for the similarly irreverent style that makes Hill House so good).

The Haunting of Hill House (1959)

The most famous of Jackson’s work is a classic haunted house story that hits all the right notes of eeriness and the supernatural, from a striking opening paragraph through to an escalating, heart-stopping climax. It’s also, however, a brilliant psychological study, in keeping with Jackson’s other work, and is utterly charming. The sense for Hill House itself is superb, a mansion that breathes its own sinister presence into the pages, but what really makes this book stand out is the characters. Their banter is clever and light-hearted, creating a great contrast between the dark foreboding and the good-spirited people it grips. Similarly, the cockiness of her companions works well to emphasise the difficulties the main character, Eleanor, has, when the mystery of the house increasingly grips her, personally, and we’re led to question exactly where the haunting stops and her own madness starts. It’s a masterwork of tension and a delight to experience in such good company.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962)

This might be my favourite of Jackson’s books for the simple fact that Merricat is an amazingly endearing character, with her little (occult) quirks and an (apparent) worldly innocence. We Have Always Lived in the Castle is underpinned by a sense of mystery and a creeping doubt that we may be dealing with an unreliable narrator, as we follow Merricat’s attempts to shun society with her sister and uncle, following the hazy details of their parents’ deaths and a growing animosity from the people in the village. Above it, it’s plain fun to follow Merricat, and the sense of danger is all the more pronounced for having such a likable main character (warning: possibly subjective!). The locals, who represent “normal” and hate the Blackwoods for being different, are rarely less than threatening. We Have Always Lived in the Castle has many moments and lines that have lived with me since reading it, from the ear-wormy nursery rhymes to daunting scenes towards the climax that seem (as Jackson achieved in The Lottery) both nightmarish and completely plausible.

The Lottery and Other Stories (1949)

This is the first of, I believe, three collections of Jackson’s short stories, as released by Penguin Classics, and it’s a great spectrum of the sort of tales explored in the novels, in miniature. The titular story, of course, is striking and memorable, dark and sinister, and held up as a horror classic, but it’s worth noting the collection at large as more a reflection on contemporary life, underpinned by bizarre or sinister details that give a general sense of uneasiness to otherwise very familiar settings. There’s a feeling throughout these stories, as similar names and ideas pop up but never quite connect, that there’s an eerie something going on behind all Jackson’s little vignettes, a through-line of the weird and troubling, but it’s just a feeling we have to live with. Many of the stories don’t have big bangs or clever resolutions, which I personally love them for – true to life, they leave you wondering, giving you space to fill in the blanks with your own worries.

That’s your lot for now – I will update with the other books as I can. If you’ve enjoyed this post please share, and if you’ve got any favourite thoughts on Jackson yourself I’d love to hear them in the comments!